Insane Photos Of Life Inside Soviet Gulag Prisons

Between 1919 and 1953, the communist government of the Soviet Union operated a brutal system of prison labor camps known as the Gulag, used to house political dissidents. Soviet citizens could receive five, ten or twenty-five year sentences for making comments unfavorable to the regime, for other political offenses, or simply because they had the wrong social background, or had the misfortune of being caught up by secret police needing to turn in a certain quota of inmates. Although the Gulag was wound up after the death of Josef Stalin in 1953, the Soviet Union continued to oppress dissidents right up to the end of the regime.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008) was a writer who was sentenced for political offenses, and who served time in the Gulag. He wrote a three-volume history of the prison system, The Gulag Archipelago, as well as many short stories and novels about different aspects of imprisonment in the Soviet Union.

Forced Labor

The first major construction project of the Gulag was the White Sea – Baltic Canal, designed to link the Soviet Union’s Arctic ports with Leningrad (now St. Petersburg). Inmates were forced to dig the canal using primitive tools and equipment.

Official and scholarly estimates of the death toll range from 12,000 deaths to 25,000 deaths. Solzhenitsyn believed the death toll reached 250,000. The entire project then had to be rebuilt because it was initially too shallow for the use of the ships it was meant for.

Construction Projects Continued

Despite the inefficiency and eventual uselessness of the project, the idea of using convicts for labor took hold, and the Soviet secret police, the NKVD, became the center of a large industrial empire consisting of prison camps, construction projects and mines.

Soviet officials were well aware of the nature of the camps, as were intellectuals and writers, who often visited projects. After World War II, the Soviet occupied states of Eastern Europe were encouraged to build similar projects using political prisoners for labor. For example, the Romanian Danube-Black Sea Canal was encouraged by Stalin in 1947, so that it would become the “graveyard of the Romanian middle class.”

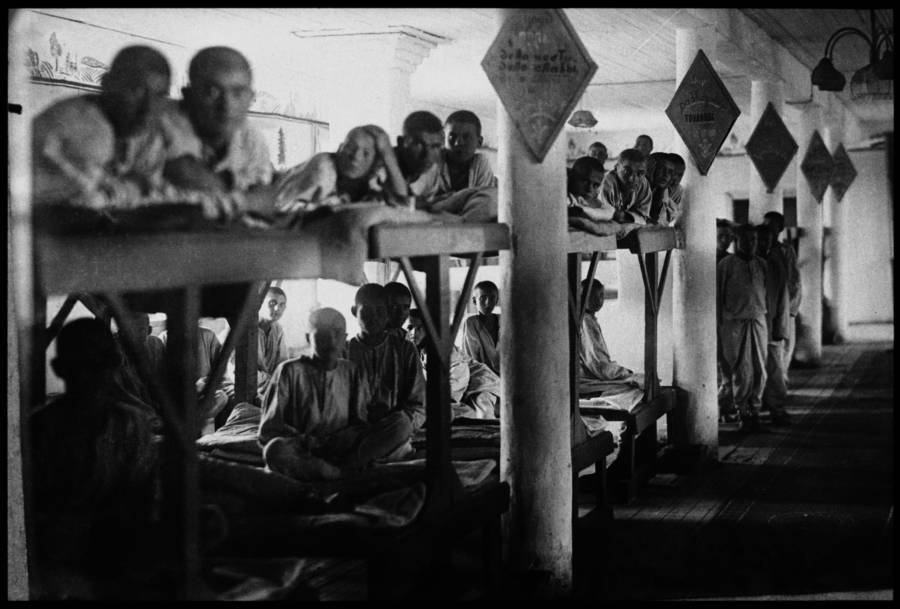

Inmate Camps

Many inmates were held in camps in mines in Siberia, especially gold mines. These camps, near or above the Arctic Circle, had extremely poor conditions and astronomical death tolls.

The gold mining camps around the port town of Magadan had a reputation for extreme brutality, though Magadan itself was sufficiently well kept to fool one American Vice-President, Henry Wallace, into calling the place a combination of the “Tennessee Valley Authority and the Hudson’s Bay Company.” Wallace clearly wasn’t shown everything about the place.

Highway of Bones

The Kolyma highway was referred to as the “Highway of Bones” because of the high death toll during construction. The highway stretched over permafrost, and so it was thought to be more efficient to simply bury the dead in the roadbed than to dig graves for the inmates who died during the construction.

The highway linked camps and settlements in the region, including Madagan and the other gold mines of the area. Estimates of the inmates who died during construction range from 250,000 to 1 million.

"Privileged" Prisoners Received Better Lodging

Specialized camps existed for certain privileged prisoners, including scientists and technicians. These camps had comparatively better conditions, and inmates were put to work on military projects designed to develop new weapons.

Soviet rocket designer Sergei Korolev spent several years in a specialized camp, before being released to work on the Sputnik project, and the first manned space flight. Soviet aircraft designer Andrei Tupolev was an even more typical case, being arrested for revolutionary activity under the Tsars in 1911, then released. He was arrested for anti-Soviet activity in 1937. He was placed in a scientific camp in 1939, given a ten-year sentence in 1940, and released in 1941, though he was not fully rehabilitated until Stalin’s death. Both men were ultimately honored by the Soviet Union for their scientific achievements.

Poor Conditions

Conditions in the Gulag were primitive, especially given the harsh climate of Siberia. Inmates were denied warm clothing and heating fuel. Food was poor quality and scarce. Many inmates starved or died of exposure.

If an inmate should be fortunate enough to survive one five-year sentence and be released, it was very likely he would be picked up and imprisoned again on fresh charges.

The Death Toll

Inmates died in droves in the Gulag, of exposure, of malnutrition, and of overwork or abuse. Guards would sometimes become frustrated and shoot prisoners who lagged behind or who did not work hard. Sometimes, death sentences were carried out in the holding cells before the inmate ever reached the work camps.

Overall estimates of the numbers of prisoners in the camps and the death toll in the camps vary. Estimates of the number of prisoners range between 2.3 and 17.6 million. The death toll has been placed as high as 2.7 million. One scholar, attempting to calculate the number of individuals who had their life span shortened by imprisonment, estimates a further 3 or 4 million died from ill health after their release. Other scholars argue that the Soviet estimate of 40 million wartime casualties hides a large number of prison camp victims.

Prison Guards

All of the prisons were guarded by NKVD officers and men, the military arm of the secret police. The NKVD also provided military police to ensure the political loyalty of the Red Army in World War II. The military staff were assisted by the common criminals sent to the prison camps, who were used as trustees and encouraged to brutalize the political prisoners among the inmates.

Many soldiers, including Solzhenitsyn, were sent to the Gulag for offenses such as writing a letter to a friend that appeared to breach military security, or for lagging behind the front line. Prisoners of war or soldiers stranded behind enemy lines could also be caught up in the net of the Gulag and sentenced to five or ten years of hard labor, if they weren’t killed outright.

Paranoia in the Gulag

Many of the Gulag’s leaders were themselves tried, convicted, imprisoned or killed in the paranoid environment that surrounded Stalin’s regime. Genrikh Yagoda governed the NKVD and thus the Gulag until he was tried and executed on charges abetted by his subordinate, Nikolai Yezhov. Yezhov, in turn, was supplanted in the same way, and suffered the same fate as his predecessor at the hands of Lavrenti Beria. Beria, a close personal friend of Stalin, managed to survive until the death of the dictator in 1953, when he was removed and executed by the other Communist leaders led by Nikita Khrushchev. Less important leaders of individual camps could be caught up in these machinations as well.

Although Khrushchev began to wind down the Gulag structure in the 1950’s and pardoned or rehabilitated many of the victims, the Soviet Union continued to repress speech, and substituted forced confinement in mental institutions for dissidents opposed to the regime right up to the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989 and 1990. Even now, forced labor for prisoners remains an option in the Russian criminal code.