Dust Bowl Photos That Still Haunt Us Today

At the height of the Great Depression, the agricultural heart of the United States was wracked by drought and a series of horrific dust storms which wiped out crops, ruined farms and destroyed lives and livelihoods. Hundreds of thousands of families were forced to leave their homes in search of a better, more stable place.

In the worst-hit states of Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, a third of the population or more was forced to move, either to parts of those states that were less badly damaged, or out of state altogether. Many of the families, called “Okies,” ended up in California.

The Beginning of the Dust Storms

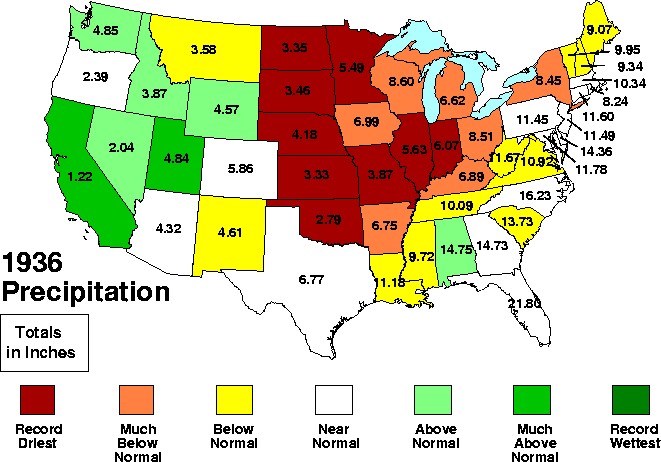

Although dust storms plagued the Midwest throughout the 1930’s, the worst years were 1934, 1936, and 1939-40. The year 1936 was marked by one of the coldest winters on record to that point, followed by an intense record heatwave that destroyed crops and killed vegetation that might have held soil in place. Windstorms whipped up by the heat turned entire states into near deserts.

Dust carried off from the Midwest spread across the entire eastern part of the country, and was reported in Cleveland, New York City, and Boston.

"Black Sunday"

The dust storms of the 1930’s were caused by unusual weather patterns in both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Cooler than normal temperatures in the Pacific combined with warmer than normal temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico to shift the jet stream, which usually brings moisture from the Gulf into the southern Great Plains.

On April 14, 1935, over twenty dust storms coincided across the entire Great Plains to create “Black Sunday,” a series of dust blizzards that blanketed the area from the Dakotas to Texas.

The Damage of the Dust

The dust storms left ruin in their path, and deep drifts of fine, windblown dust that wiped out crops, covered buildings and destroyed machinery. Farmers, already suffering from low prices for their crops, and heavy mortgage and property tax burdens, could not continue to work the land after the loss of their harvest.

The destruction was intensified by farming methods that removed grass and cover crops from farmland and by deep plowing techniques which destroyed weeds, but which also loosened the soil. When dry weather combined with high winds, no plants were alive to keep the soil from blowing away.

People Were Forced To Abandon Their Homes

The widespread destruction of farms and farming communities forced hundreds of thousands of families to move, seeking a new life. At the height of the Depression, work was hard to find, and conditions were harsh. Even the slightest mishap could escalate into a major crisis for the impoverished migrating families from the Midwest.

The vast scale of the migration placed a strain on both charitable and government agencies designed to help the poor. Many towns turned away migrants with signs saying that there was no work and that they could not help their own poor, let alone the migrants.

Displaced Families Must Find New Work

Many farm families, who had been land owners with their own farms before the Dust Bowl, were forced into tenancy, as sharecroppers, or migratory labor on the road following crop harvests from south to north every year. California, with labor-intensive fruit and vegetable farms, and orchards, provided one source for work for displaced families.

At the time the picture was taken, Florence did odd jobs in hospitals and restaurants and followed crops throughout California and Arizona. In the cotton fields, she would pick between 400 and 500 pounds of cotton from dawn until nightfall. She later said, “I done a little bit of everything to make a living for my kids.” She was the sole income for her family after her husband died of tuberculosis in 1931.

The Migrant Camps

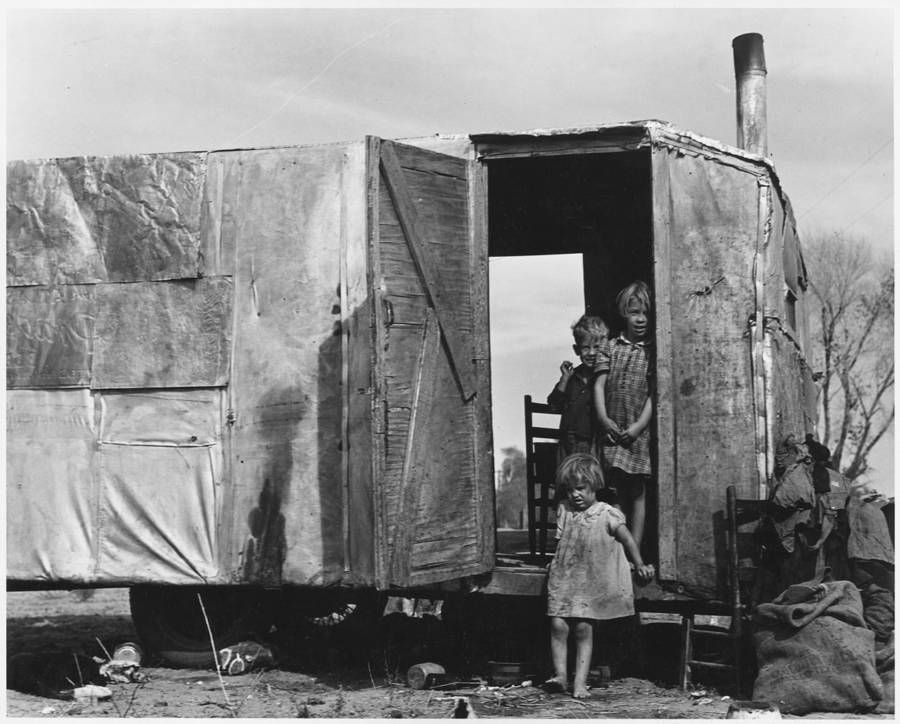

Conditions in the migrant camps could be spartan for families which had lived in perfectly ordinary farm houses a few weeks or months before. A trailer patched together with odd pieces of sheet metal and a simple wood stove might house parents and many small children. Shanty towns for migrant workers grew up near fields in many towns of California.

The original title of the piece,”Dirty Children,” depicts the filth and squalor that pervaded such camps, but much of the problem arose from the lack of running water or sanitary facilities. Virtually all of the farms the migrants left would have had pumps operated by windmills to provide an ample supply of water for washing and bathing.

Making A Living in California

The migrant camps left their surrounding environment almost as barren as some of the towns in the dust bowl. California did not suffer the same intensity of drought and dust storm as the Great Plains. However, traffic from the newcomers quickly reduced the surrounding land to waste around the camps, and put pressure on local resources and water supplies.

Most of the migrants remained in California after the Dust Bowl. The onset of World War II provided steady and reliable jobs for many in the shipyards, airplane factories and war industries of the state. California remained a popular destination for Americans seeking a better life, and grew to be the most populated state in the United States, but at the cost of intensive land use and urban sprawl, which brought with it heavier traffic and water usage in a state already very dry.

Soil Conservation

Congress enacted soil conservation measures as part of the New Deal to help recover farm land damaged by the Dust Bowl. One witness, testifying before a Congressional committee, was helped by a dust storm which reached Washington DC itself in 1935. “This, gentlemen, is what I have been talking about. The Congress enacted the Soil Conservation Act in response, and the Soil Conservation Service has been a part of the Agriculture Department ever since.

The Civilian Conservation Corps began reforestation and grass planting efforts and attempted to restore the native vegetation in the Great Plains. While farm values remained low for many years, productivity resumed when the climate cycle changed, and when the onset of World War II restored profitability for many farmers in the United States. Farm operations grew larger, however, thanks to mechanization, and families did not necessarily return to the old farmsteads.

The Dust Bowl in Popular Culture

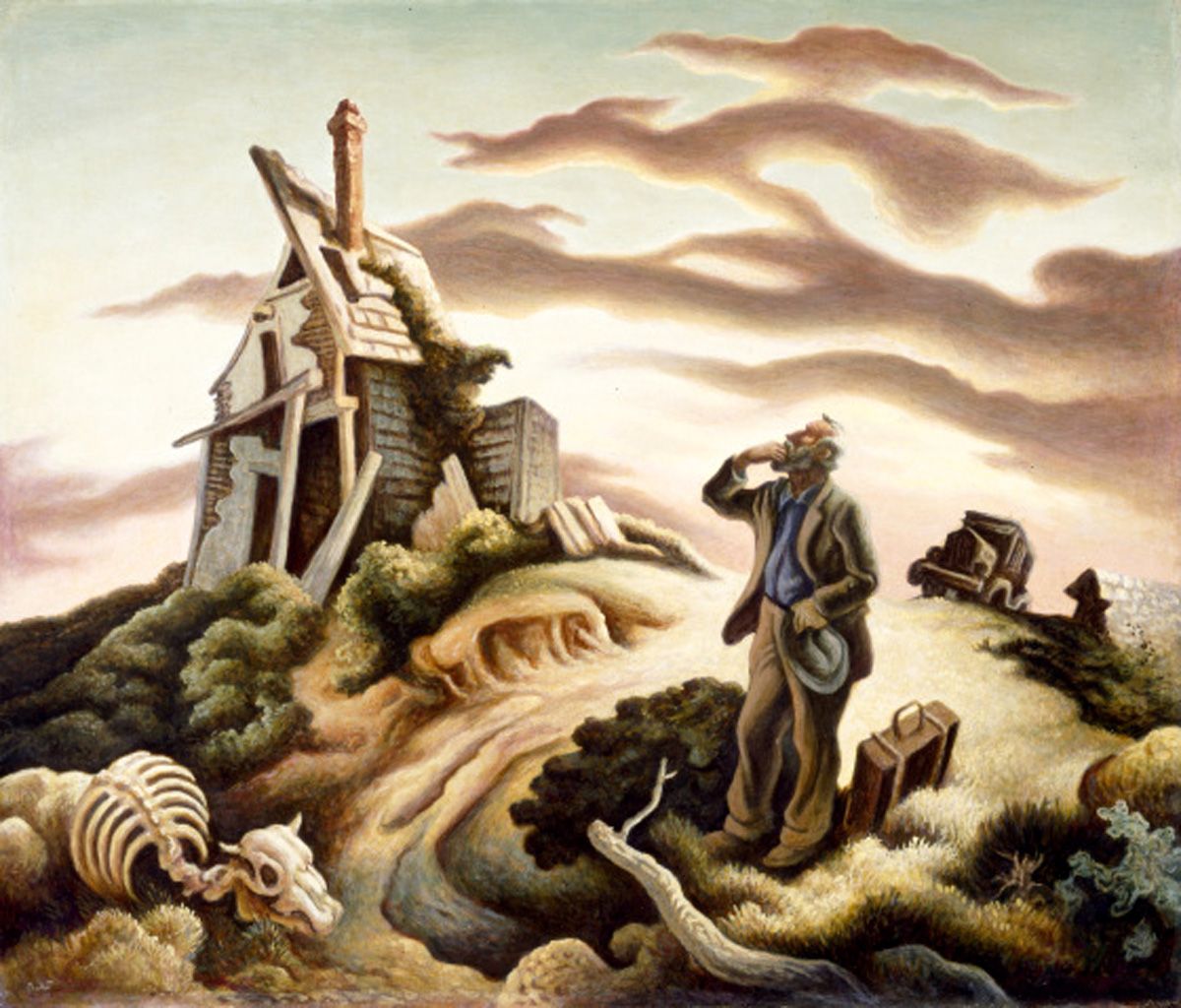

The Dust Bowl had an enduring effect on the American psyche, reflected in popular culture as well as in art and literature of the time. John Steinbeck’s novel The “Grapes of Wrath,” depicted the plight of devastated families migrating in search of a better life in California. As late as 1969, the musical “110 in the Shade” by Tom Jones and Richard Schmidt hearkened back to the period.

Paintings of the period reflected the mood. Thomas Hart Benton was an American regionalist painter in Missouri at the height of the Dust Bowl. His painting, Prodigal Son, offers a twist on the biblical story. The son arrived too late, and returned to see his home farm wiped out by dust.